帶貓貓去海灘玩,太陽很大沒有擦防曬霜,回家肩膀疼了兩天,然後開始脫皮。貓貓看見了,今天晚上洗澡的時候跟媽媽說,“我其實挺欣賞爸爸的。” 媽媽問他為什麼,他說,“因為他會蛻皮”。

貓貓語錄

吃飯的時候說,“我現在比螞蟻還瘦!”

貓貓語錄

自己一個人躺在沙發上唱,“香蕉不是我的愛,西瓜才是我的愛。” 哪裡學來的。

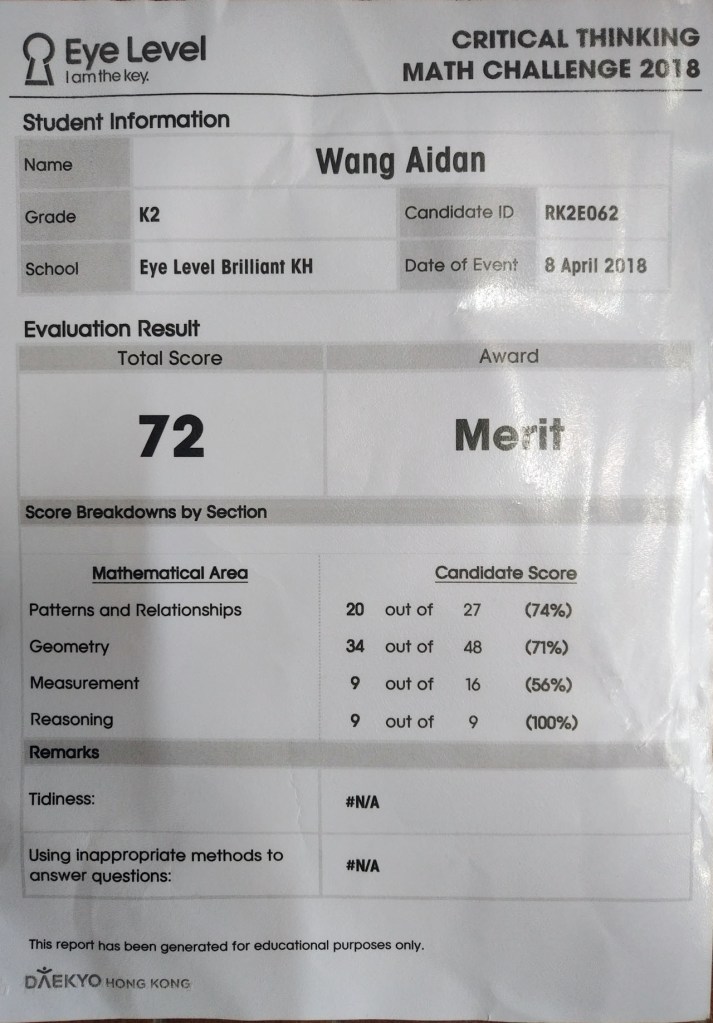

May 13, 2018

人生第一試,看来智商沒有遺傳到爸爸。

昨天收到Victoria的拒信,十幾家國際學校面試基本上全軍覆沒,都是第一輪都沒過。主要問題是完全不聽招呼,任何事情喊他多少遍都當耳邊風,照做他自己的事情。去圍棋課,英語課,數學課和網球課都被老師投訴。都是一開始都很喜歡他,可是後來完全不能manage. 上次去英語課家長會,老師說,If it’s just him not following my instruction I can handle, but other kids follow his behavior too and suddenly the whole class in in riot, I just can’t have that. For example I told him not to pour all the food out during break, he kept pouring it and looked at me while he was doing it, as if saying what are you gonna do about it? 網球課也是,教練跟他說,this is a place to learn, if you don’t respect me then you are not welcome here. 說了三遍,我坐在旁邊不高興了,站起身來把他拉走了。

只有個ESF的offer。那天去ESF Quarry Bay School面試,本來是面試waiting list,貓貓進去了以後,老師來要家長談一下。輪到我們的是副校長,問我們,對孩子有什麼期望。我說,“I recently read Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh, and one sentence really resonated with me: ‘If a man has done enough in art and music to make me feel I can trust him with my life in a time of crisis, then he’s successful in my eyes.’ ” 副校長聽了,跑去教室坐在貓貓旁邊看他畫畫,下午就直接給了offer。要不然真不知道到哪上學。

貓貓語錄

貓貓要拿個冰激淋吃,阿姨說 You ask Popo first. 他跑去問阿婆,“阿婆我可以看書嗎?” 阿婆說好啊。他跑回去跟阿姨說,“Popo said Yes!”

April 28, 2018

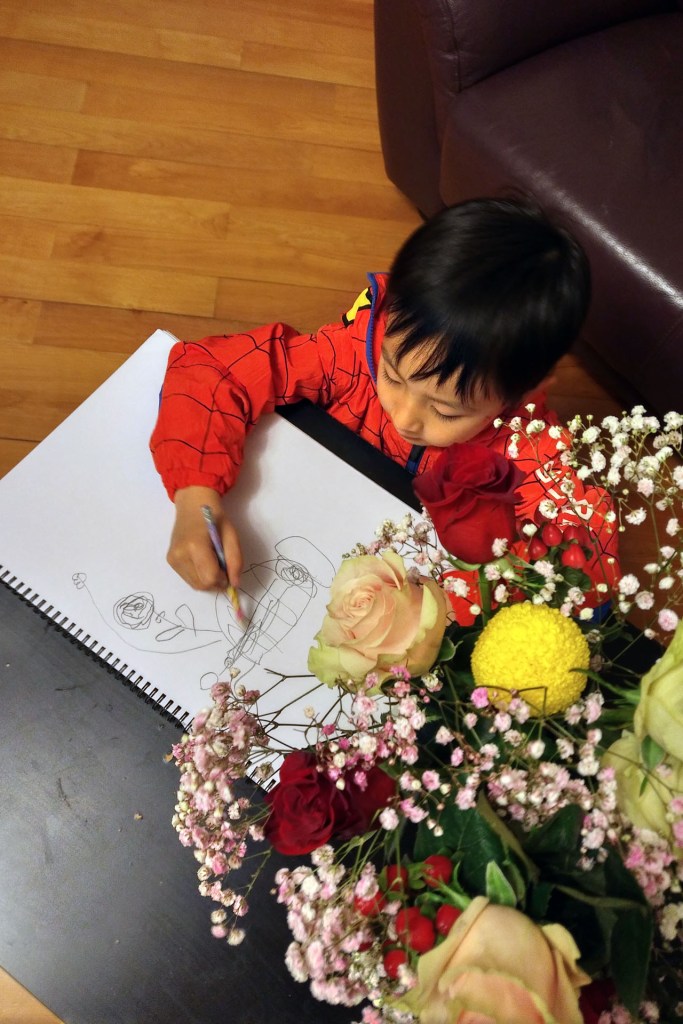

畫畫越來越有型了。

貓貓語錄

貓貓幼兒園最近教了一個愛護環境保護海洋生物的主題,他現在就拒絕吃魚。每次吃飯看見有魚就說,“讓打漁的人不要打魚了,很疼的。” 昨天晚上在冰箱裡翻出了一盒冷凍的蝦,泡了幾個蝦在水裡。今天早晨起來第一件事就是跑去看,說,“我看看他們活過來沒有。”

貓貓語錄

媽媽教貓貓不要評論別人的長相,晚上他睡著前迷迷糊糊的突然想起這事,在那兒自言自語,媽媽錄了一段發給我,他說,“如果你看見一個人哈,ugly的話,就不要理他,just let it be。If you see ugly people just let it be. If he looks like a dinosaur, don’t say this people very old啊,don’t say this. If people look like a bunny, don’t say that. If you say that, they say you are ugly. So don’t say that. If people are very old, just let it be. Just let it go. ‘Oh this people very old, this people look like a bunny’’, don’t say that. If police see that they catch you. So don’t say that, be friends.”

March 4, 2018

過生日帶貓貓去深圳找了個酒店,跟奶奶過了兩天。

February 7, 2018

During the month I read “The Road”, the first cold wave of the winter hit Hong Kong and Maomao fell with a fever that quickly shot over 40 degree Celsius. At night I set alarms to take his temperature every hour and half, and it took me a while to fall asleep again every time. As I laid in the dark listening to his breath, hot and heavy like that of a wounded little monster trying to break through some invisible wall, I thought of the opening sentence of the novel in which the man woke up in the dark and cold of the woods and reached out for his son sleeping beside him. Or maybe I dreamed that scene, having sunk into REM so quickly due to exhaustion without even realizing it. And I thought how frail it is this thing we call staying alive, in particularly together, just a man and his son through the night, in an all-out apocalypse or a mere cold spell.

In the morning on the subway, having left Maomao at home to recuperate, I found myself ruminating over the last scene of the man. I kept imagining what was going through his mind as he closed his eyes on the world for one last time. Was he at peace at last, having exhausted every ounce of his own existence to prolong that of his son, unrelentingly, always more unrelentingly than the onslaught of the apocalypse as long as he could and did hack it, till the last breath? Or was he drowning in sheer terror in realizing that his wife was right all along, that in the end he could not help but left his son to die alone out in the open, most likely in some unimaginably gruesome fashion, and all the more cruel on his part because he chose to raise him into a conscious human being capable of experiencing and understanding such inhumane horror and pain?

It’s not by design that I picked up “The Road” right after “The Way of All Flesh”, and it surely didn’t help the crippling doubt that seeped in through that long and often tedious read. Many times I had lashed out on Maomao due to impatience or worse frustration totally unrelated to him, and quickly tried to ameliorate the guilt by some ad hoc and self-righteous justification. But theoretically, that’s something one can strive to atone, something that unbounded love and vigilant self-restraint can hopefully prevail over. What McCarthy did here is an ultimate denunciation of love’s delusion and fallacy. Like any tragedian worth his salt, he presented that love so beautifully and movingly before shattering it right in front of your eyes. Love, as we may call it, in its most bare-bone and courageous form, is at the same time hubris and selfishness, at all time: what makes you think your love can triumph over the evil of human nature? In the typical, ruthless McCarthy fashion (think of “the kid” in Blood Meridian in the end), he killed the man, and left the silent accusation hanging in the cold and dark air before dawn: Look at your son. what have you done, what now. But the ending, so faint-hearted and jarring with the rest of the book, is in itself an admittance of defeat and a parody of the weakness of human nature — even he, who brought to life “the Judge” that still terrifies me to my wit’s end whenever I think of it, cannot bring himself to properly kill off the boy.

It’s probably inevitably morbid to call the book beautiful. Yet time and again I admired the man, not when he was fighting off a gang of cannibals to save his son but when he stood in the bleakness of a dead world and saw beauty:

“Dark of the invisible moon. The nights now only slightly less black. By day the banished sun circles the earth like a grieving mother with a lamp.”

“He walked out in the gray light and stood and he saw for a brief moment the absolute truth of the world. The cold relentless circling of the intestate earth. Darkness implacable. The blind dogs of the sun in their running. The crushing black vacuum of the universe. And somewhere two hunted animals trembling like ground-foxes in their cover. Borrowed time and borrowed world and borrowed eyes with which to sorrow it.”

“He thought each memory recalled must do some violence to its origins.”

“Years later he’d stood in the charred ruins of a library where blackened books lay in pools of water. Shelves tipped over. Some rage at the lies arranged in their thousands row on row. He picked up one of the books and thumbed through the heavy bloated pages. He’d not have thought the value of the smallest thing predicated on a world to come. It surprised him. That the space which these things occupied was itself an expectation.”

Reading these excerpts over and over again I thought the apocalypse setting notwithstanding, it is in the end the same and only thing that is in a father-son relationship: hurling a man’s memory into the future, “carrying the fire”, always remembering being a human and how it is to be one. Two nights ago as I put Maomao to sleep we somehow got into the abstract notions of genealogy. He asked, “Who’s grandpa’s dad then?” I said, “My grandpa. My grandpa is the dad of your grandapa.” He was like, “Huh?” and started laughing. He kept trying to repeat what I said and couldn’t and found it enormously amusing. This went on for a good five minutes before he got tired and snuggled up to me and closed his eyes in satisfaction. Holding him I thought of the last words of the man:

Look around you, he said. There is no prophet in the earth’s long chronicle who’s not honored here today. Whatever form you spoke of you were right.

The man took his hand, wheezing. You need to go on, he said. I cant go with you. You need to keep going. You don’t know what might be down the road. We were always lucky. You’ll be lucky again. You’ll see. Just go. It’s all right.”

February 01, 2018

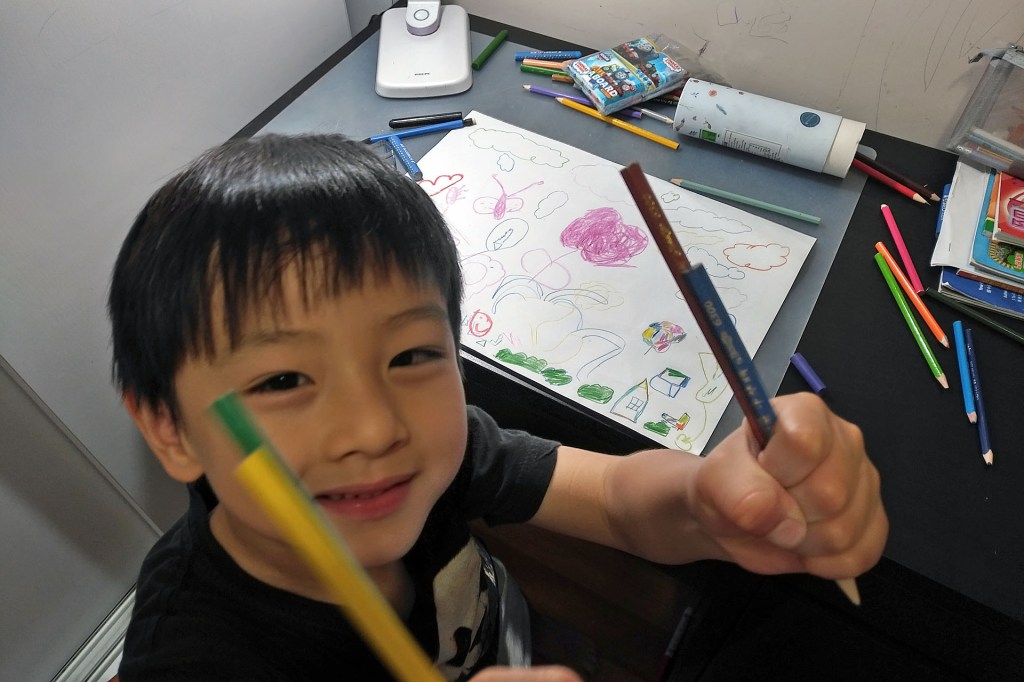

畫畫課回來意猶未盡。

January 13, 2018

寫生。