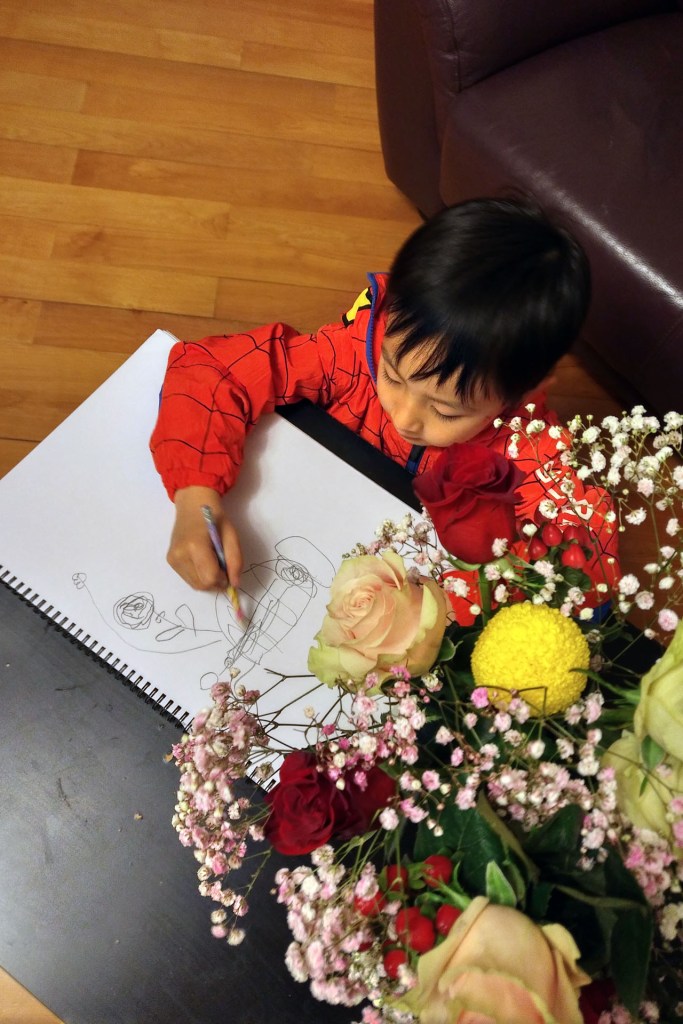

寫生。

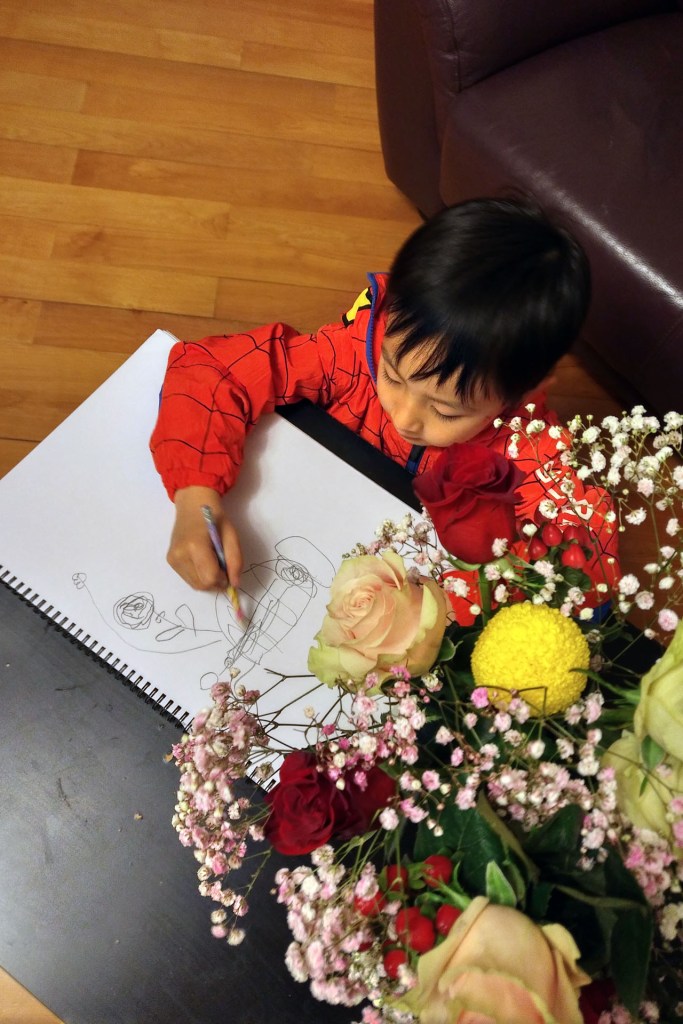

寫生。

發燒沒好我也就請假在家陪他。他說,“爸爸我們來玩個遊戲吧”,我以為又是躲貓貓之類的,結果他把圍棋拿來的。我想正好學了這麼久還不知道他到底學會了什麼。他把棋盤打開,堅持讓我持黑子。我心想老師還不錯除了教棋道還教棋禮。我落了一子,他馬上用兩個白子兩邊夾住。他看著我盯著他,就很自然而然地說,“有時候是可以一次走兩步的,有時候。” 我說為什麼?他說,“因為老師經常看不見啊。” 所以下了五分鐘基本上盤面上我就變成被橫掃的局勢。

發高燒兩天,只能玩點斯文的了。昨晚帶他去書店選拼圖,他一眼看中一定要這個。回來路上問我,"爸爸!這些都是什麼人啊。"我說是希臘的哲學家。他問希臘是什麼,我說是古時候的一個地方。他於是想了想說,"爸爸!你是我們家的哲學家。"我很欣慰地謙虛了一下,說是嗎。他說,"對啊!因為你經常給我折飛機,折青蛙!"

貓貓不喜歡做作業,有次我帶他在馬路上走看見修路的,他在那裡看了半天,我跟他說,如果不做作業考不上小學,就只有去讀鋪瀝青的學校長大了去鋪瀝青養活自己,因為只有瀝青學校不考試。前幾天從日本回來,在機場他問媽媽,“媽媽在機場工作要不要做作業的?” 今天路過麵包店又問我,“爸爸,做麵包要不要做作業的?” 估計是覺得鋪瀝青這個工作不太理想,在做職業規劃。智商不夠的只有情商補了。

“The Way of All Flesh” is a book that’s good to read, in a similar sense that broccoli is said to be good to your health. You probably nod along the way, and all-in-all you are glad you read it after you read it, but it’s also highly likely that at no point during the reading you truly enjoyed it. I found the writing style rather bland, in spite of occasional attempts at British humor. The protagonist, Ernest, to me is unrelateable, if not unlikable. It’s never clearly stated what it was that his godfather and aunt saw in him that set him apart from his supposedly utterly despicable siblings, not a word was said about his literature talent until suddenly he became this avant-garde publishing writer in the very last part of the book. To summarize the plot of the book, basically it’s a laundry list of how Ernest screwed up his uninspired life at every turn in fittingly banal manners, until at last he duly inherited the big sum of money, at which point he abandoned his children to total strangers and spend the rest of his life traveling alone and publishing books nobody read.

But plot points are not the point here, it’s the subject matter that matters. Samuel Butler displayed his wisdom in an impressively calm and confident manner, through his analyses of the father-son relationship in the Victorian Era, and what he said remains highly relevant today, to the point I constantly felt obliged to take a step back and think about my ways of handling Maomao as I read through his often scathing commentaries:

“To parents who wish to lead a quiet life I would say: Tell your children that they are very naughty—much naughtier than most children. Point to the young people of some acquaintances as models of perfection and impress your own children with a deep sense of their own inferiority. You carry so many more guns than they do that they cannot fight you. This is called moral influence, and it will enable you to bounce them as much as you please. They think you know and they will not have yet caught you lying often enough to suspect that you are not the unworldly and scrupulously truthful person which you represent yourself to be; nor yet will they know how great a coward you are, nor how soon you will run away, if they fight you with persistency and judgement. You keep the dice and throw them both for your children and yourself. Load them then, for you can easily manage to stop your children from examining them.”

Now, every time I try to discipline Maomao and rationalize my (what must seem to him) sudden flare of anger with him, I think about this passage and can’t help feeling like a fraud. It never occurred to me before to imagine how Maomao must have felt from the receiving end when I lost my temper and yelled at him, how terrifying my face must have looked when I bared down on him. Yet the vague awareness that at such moments he would take the tirade spewed from the red face out of sheer anger all as literary truth is enough for me to make full abuse of it. Reading this paragraph is thus like being caught read-handed for cheating.

I often think that my love for Maomao, the kind of exuberant and self-negating love, has many elements that are rudimentary to faith. One beef I always have with religious people is the (admittedly often unintended) air of superiority, stemming directly from the absolute certainty that they are in the right. It’s my instinct to always be open to counter arguments, to have the baseline assumption that there is no absolute truth, especially when it comes to personal choice. But with Maomao I can now see that such certainty does have the potential to bestow happiness and fortitude in the face of adversity. And it makes devotion and sacrifice an indisputable pleasure. It goes against a person’s basic survival instinct and you almost look forward to opportunities to sacrifice yourself for his sake, big or small. But the absolute certainty that you are doing the right thing is of course at all time counter-weighted by the crippling doubt of not knowing if you are doing it the right way. The way that is supposedly intended by the object of worship, or if it “pleases the God.” “Common sense” is a moot concept to faith, not being founded on rationality. Likewise I fumbled along with Maomao, making up rules and regulations on the fly and raising him on a generally ad hoc basis. I regret every time I yelled at him with the intensity I’d repent a sin. And trying to gauge his nebulous conscience feels equally futile to Job’s grapple with God’s intention.